A Noteworthy Federal Memo

The EPA signals its intentions regarding PFAS under “Superfund,” and research on where these chemicals go inside us

Welcome to ContamiNation. Subscribe for free to receive it monthly.

Many people working in water utilities, sewer districts and fire departments are among those who welcome recent federal action on PFAS chemicals. But there’s anxiety about what those regulatory changes might mean for some local entities and landowners. So while this month’s lead story sounds—and admittedly is—a bit wonky, it provides information that local communities need to know and may have missed.

When the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced in April that it was designating two of the most studied and problematic PFAS (or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances), PFOA and PFOS, as hazardous substances under “Superfund” or CERCLA (the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act), many media stories overlooked an essential part of the agency’s message. A separate EPA memo written to guide its staff received little press, despite being crucial in clarifying what this designation may mean for those unwittingly caught in the PFAS rip tide.

Whether internal agency guidance will be sufficient to protect innocent parties from lawsuits is the subject of heated debate. Groups representing water and wastewater utilities, landfill operators and others are lobbying for legislative exemption from CERCLA liability for PFAS releases, while some environmental advocates counter those arguments.

Even as that controversy continues, more people need to know what’s in the EPA memo. Some key points follow for those who prefer a 500-word synopsis to the 11-page agency version.

The “PFAS Enforcement Discretion and Settlement Policy Under CERCLA” memo clarifies who the federal government will target for enforcement actions: “EPA will focus on holding responsible entities who significantly contributed to the release of PFAS into the environment, including parties that manufactured PFAS or used PFAS in the manufacturing process, federal facilities, and other industrial parties.” Federal facilities include those of the U.S. military, which in the 1960s helped develop PFAS-laden Class B firefighting foam and has been its largest user.

The memo is equally clear about who falls outside the agency’s enforcement sights, “including, but not limited to, community water systems and publicly owned treatment works, municipal separate storm sewer systems, publicly owned/operated municipal solid waste landfills, publicly owned airports and local fire departments, and farms where biosolids are applied to the land.”

The agency affirms a strong commitment to environmental justice, working to ensure that what it terms “primary responsible parties” (like a PFAS manufacturer or paper mill) investigate and clean up PFOA and PFOS exposures in “overburdened communities that may be disproportionally impacted by adverse health and environmental effects.”

The EPA acknowledges the concerns that entities like water utilities and wastewater treatment plants may have about getting sued by “primary responsible parties,” and it spells out two means by which it can offer “some measure of litigation and liability protection.” In its settlement with the primary responsible parties, it may secure a “waiver of rights” that prevents them from pursuing any financial contribution from particular “non-settling” parties. Or local entities can enter directly into a settlement agreement with the agency that is not tied to enforcement, which would exempt those entities from claims related to that settlement.

The “limitations and contingencies” section notes that EPA’s discretion with enforcement hinges on cooperation, and responsible parties are still obligated to report releases of PFOA and PFOS. The agency is not limited in its ability to enforce CERCLA where any responsible party’s actions or inactions “significantly contribute to, or exacerbate the spread of significant quantities of PFAS contamination,” thereby presenting “an imminent and substantial endangerment to public health.”

The memo acknowledges the inequities in the costs and consequences of PFAS falling on those who did nothing to create the problem, and signals the agency’s intent to help redress those inequities rather than exacerbate them. However, it bears noting that neither the agency’s staff guidance nor its decision to include PFOA and PFOS under CERCLA will necessarily bind future administrations.

Research: Tracing Where PFAS Go Within Us

As medical research reveals health risks from per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) even at extremely low levels, there’s growing interest in wider access to PFAS blood testing. In 2022, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine released guidance recommending that clinicians offer blood testing to people with a history of elevated PFAS exposure (see this study for more on possible exposure routes).

The medical community still has a limited understanding of where PFAS go beyond the bloodstream. A new study by researchers in Denmark analyzed tissue samples for four PFAS (the legacy PFOA and PFOS compounds, another long-chain compound, PFNA and a shorter-chain one, PFHxS), and found that concentrations in whole blood did correlate with levels in nearly all the organs tested—liver, kidney, lung and spleen, with the liver “possibly acting as the main organ of retention,” they wrote.

It was a sobering discovery for study co-author Dr. Philippe Grandjean, a professor of environmental medicine at the University of Southern Denmark and a long-time international PFAS researcher. “We regard PFAS [as] multiorgan toxicants [since] they can interfere with metabolism, hormone functions, immune functions, etc.,” he wrote in an email. “Now we see that they can actually reach essentially any organ of concern.”

The only exception was the brain, where levels were markedly lower than in the blood. Grandjean cautioned that the anonymized tissue samples (which came from forensic autopsies of 19 individuals in Denmark who had died unexpectedly) were all drawn from adults: “Our worry is that PFAS may more easily pass the fetal blood-brain barrier than in adults, and PFAS neurotoxicity remains a concern, especially in early life.”

Tissue sample studies, the researchers wrote, may not accurately reflect the organ from which they came. And “because the blood concentrations do not closely reflect the organ concentrations, we need to consider blood tests tentative biomarkers of PFAS elsewhere in the body,” Grandjean wrote.

Researchers don’t yet know how the thousands of PFAS variants act within different organs or how long they might linger there. Newer, shorter-chain PFAS have been marketed as safer because they have a shorter half-life in blood, Grandjean observed, but “the possibility exists that the half-life may be much longer in certain organs, which may therefore be vulnerable to toxic effects despite the wash-out from blood.”

News of Note

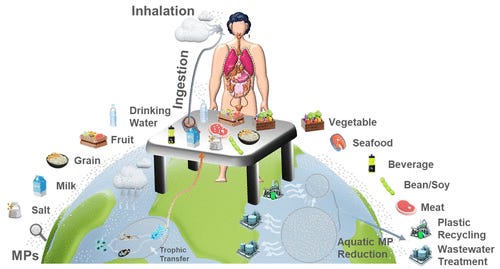

Two systems engineers at Cornell University provide a fascinating and disturbing global look at the ingestion and inhalation of microplastics if you’ve been wondering how countries compare. Indonesia tops the list for ingestion and China and Mongolia tie for highest concentrations inhaled. Eradicating most aquatic plastic debris could greatly reduce those concentrations, the research suggests.

“Unknown PFAS contamination is as widespread as legacy PFAS,” researchers in China concluded, after completing a study that used machine learning to identify the breadth of PFAS present in wastewater samples. The networking algorithm detected 733 compounds, 39 of which had not previously been identified in environmental media. In their words, the findings “suggest that the risks of unknown PFAS should be scrutinized and carefully reevaluated.”

New research may have you rethinking synthetic clothes, if you aren’t already. On the personal risk front, researchers used models to trace how chemicals from microplastics can pass into our skin, particularly when it’s sweaty. And on the planetary side, an article in Nature Communications documents the staggering macro- and microplastic global waste from synthetic clothing. The first figure conveys a lot, even if you don’t have time to read the piece.

And, just published yesterday, a study done by scientists at the University of Southern Florida finds that the mass of fluorine leaving landfills in volatile PFAS —essentially gaseous emissions—is as high or higher than the mass in leachate, confirming a largely unstudied pathway of these persistent compounds cycling back into the atmosphere (see the research piece in the May issue of this newsletter on PFAS in rain).

Good Riddance

It’s time for a cleaning utensil changeout, according to a new study that found “scrubby” sponges (where an abrasive side is made of melamine) can shed a stunning number of microplastic fibers as they wear. Sponges with coconut or walnut fibers, stainless steel scrubbers and natural bristle brushes offer better options.

Good Resources

Be prepared in coming months, to learn a bit more here about PFAS in firefighting, since I’m researching that topic as a member of the inaugural cohort of Pulitzer Center StoryReach U.S. fellows. I’ll share more on that project as it progresses, but in the meantime this webinar from the International Association of Fire Fighters (IAFF) introduces the topic—with interesting perspectives from firefighters who have done extensive research on PFAS, two academic researchers and the IAFF’s chief medical officer.

And if you’re looking for outdoor gear without PFAS, journalist Alden Wicker, author of To Dye For: How Toxic Fashion Is Making Us Sick and How to Fight Back, has done much of the work for you in a recent piece in her newsletter, EcoCult.

Thanks for reading!